Contracts, corruption and climate

How the Global South needs to re-design its power contracts to save money and the environment

In the power sector, there unfolds a complex story where corruption and climate intertwine, showing how tackling the former can help the latter.

How is electricity purchased in developing countries?

In developing countries, competitive electricity markets seldom exist. Most electricity is sold through 20-30 year contracts known as power purchase agreements between a state-owned utility (which buys the electricity on behalf of the people), and an independent power producer.1 This means that in order to understand the power sector, we need to know what is inside power purchase agreements.

What is the problem with power purchase agreements?

Power purchase agreements are cost plus contracts which means that the independent power producer can bill the state-owned utility for all increases in input costs. If the cost of coal goes up, 100% of this increase is borne by the state-owned utility, which passes this on to households by charging higher prices for electricity.

If the state-owned utility cannot charge higher prices because it is politically constrained, then it just accumulates debt until it’s bailed out. Even in this scenario, it’s the citizens who ultimately pay.

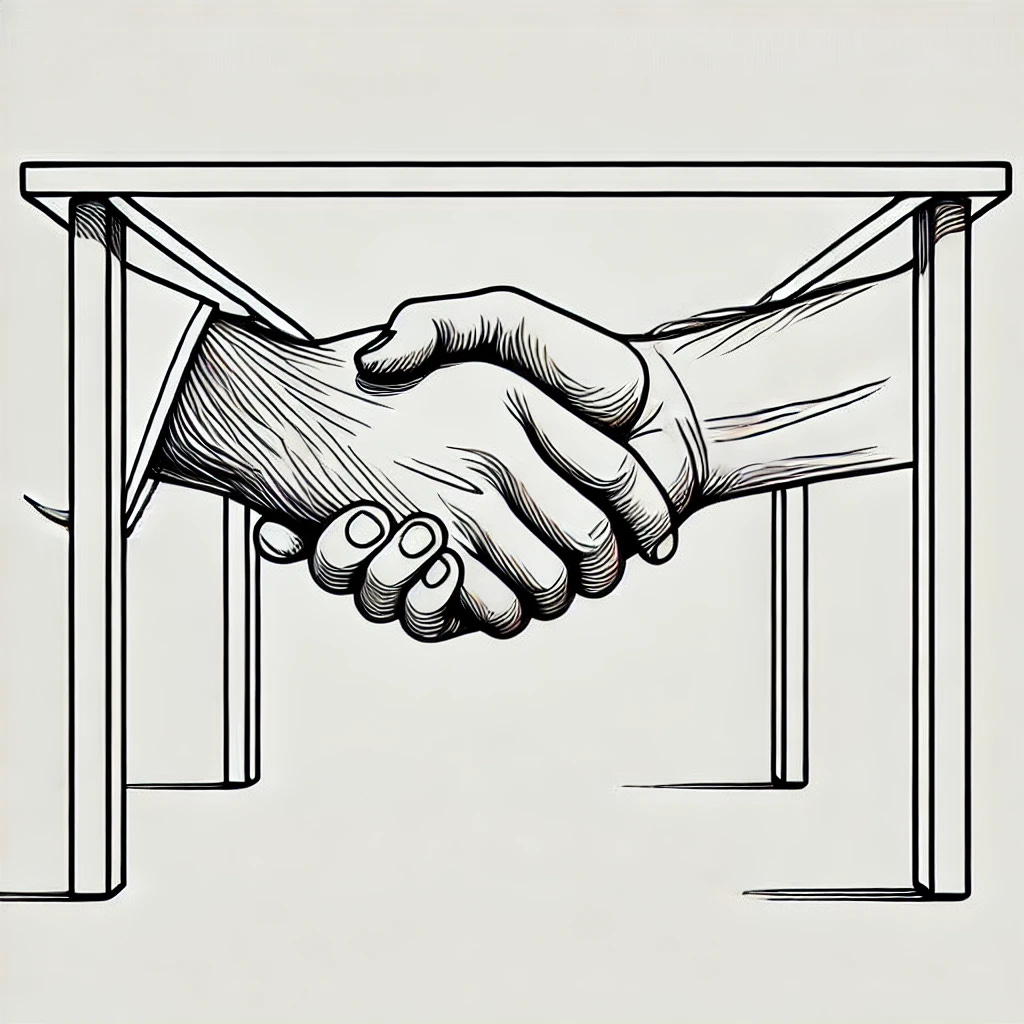

Why does cost plus contracting lead to corruption?

Imagine a situation where you get reimbursed unconditionally. This creates a temptation to doctor receipts and claim you're spending more than you actually are. This is exactly what's happening in the electricity sector. Independent power producers are claiming they're using more expensive coal and pocketing the difference in price as excess rents.2 Even in countries where coal is relatively new, like Pakistan, it has been found that Chinese-operated coal plants are sourcing coal that is substantially higher than market rates.3

Why does this lead to environmental degradation?

The price of fossil fuels can rise due to both market and policy-driven factors. On the market side, most of the easy-to-exploit mines have already been tapped into, leaving the mines with higher extraction costs for further development. The transportation of coal also adds further costs. On the policy side, taxing climate and pollution externalities would also raise the price of fossil fuels.

But if an independent power producer can pass on all of these cost increases to the state-owned utility, then it has no incentive to increase its fuel efficiency or pivot to clean energy alternatives.4 What's more, these contracts last for decades, locking in more expensive polluting technologies well past their market and social expiry date.5

Why does cost plus contracting lead to inequity?

Even if there is no lying about input costs, this contract structure is a transfer of risk from the independent power producer to the citizens of the country. Rather than bear the risk of fuel price itself, the independent power producer shifts the entire burden to the state-owned utility. Across the Global South, the power sector has consequently been racking up crippling debt.6

The way forward

Cost plus contracting necessitates excellent governance and auditing. Time and time again, we have seen this contract structure fail because it allows independent power producers to steal from the state.7 There is an urgent need to put in place stricter auditing procedures to tackle the ongoing rampant corruption. The global call for contract transparency has now begun.8

There is also a deeper question of whether this is even a fair distribution of risk. It's hard to find other sectors in the economy where a firm can contractually pass on 100% of the increase in input costs. There is a spectrum from 0 to 100% and perhaps states should push back and say independent power producers ought to be footing some of the bill for their own input costs.

This is the first post in a series that will look at contracts, corruption, and climate. Subscribe to stay tuned!

Even in countries where there is a competitive market, like India, it only accounts for 10% of total electricity by volume.

McCrum et al. (2023). The mystery of the Adani coal imports that quietly doubled in value. Financial Times.

Coal Corruption (2024). Business Recorder.

Srivastav, Jindal, Isaad, Dewi, Wagner and Fankhauser (forthcoming). Contracts over economics: exiting fossil fuel power purchase agreements.

Srivastav (2023) How are energy contracts affecting the transition to net zero? Economics Observatory.

Srivastav (2024) Why Pakistan is locked into overpriced and environmentally damaging power sector contracts. VoxDev Talk.

Ibid.