The man behind the monopoly

John D. Rockefeller, the richest man in America, is known for his oil refinery business, Standard Oil, but his greater legacy is an unparalleled level of market dominance.

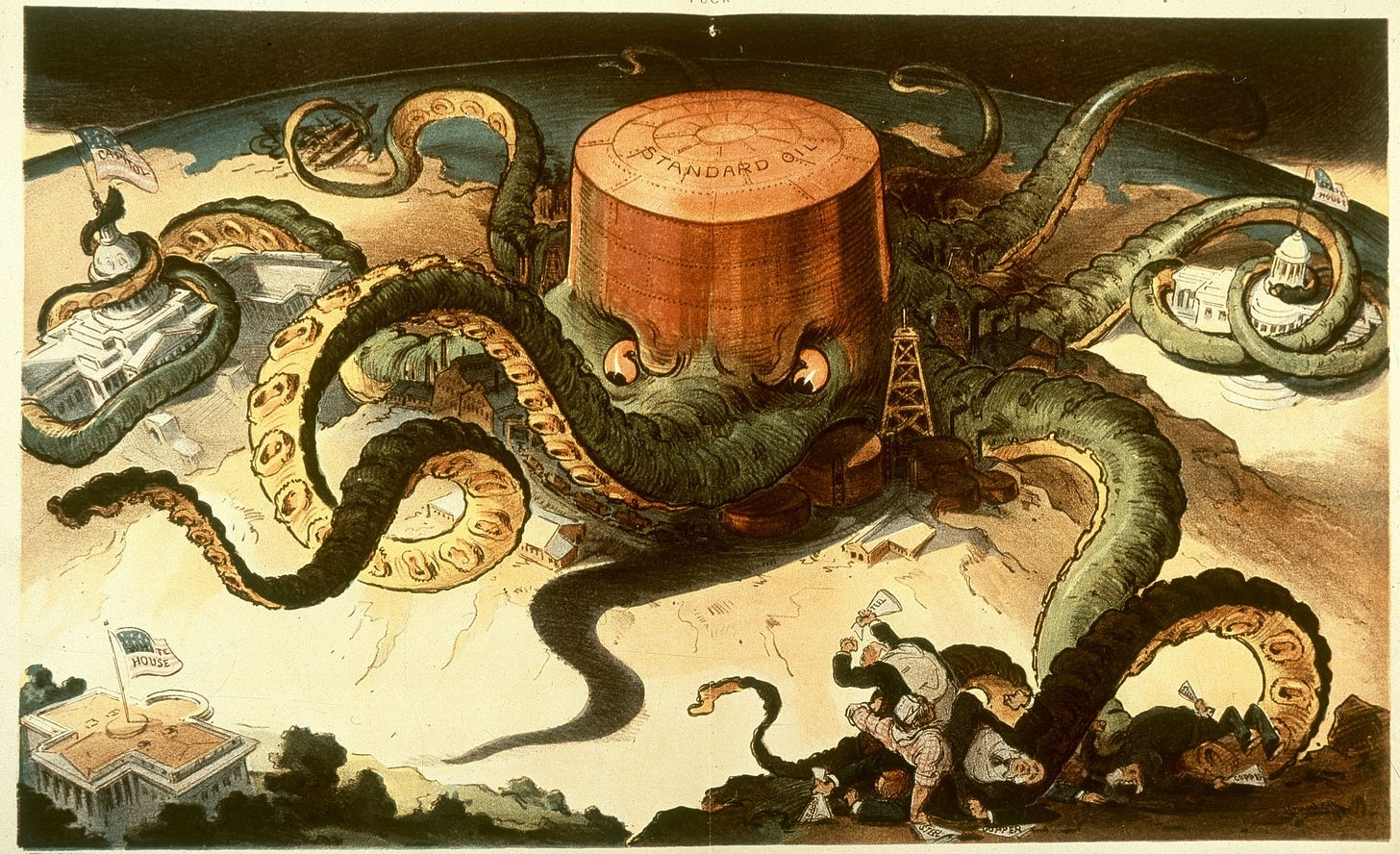

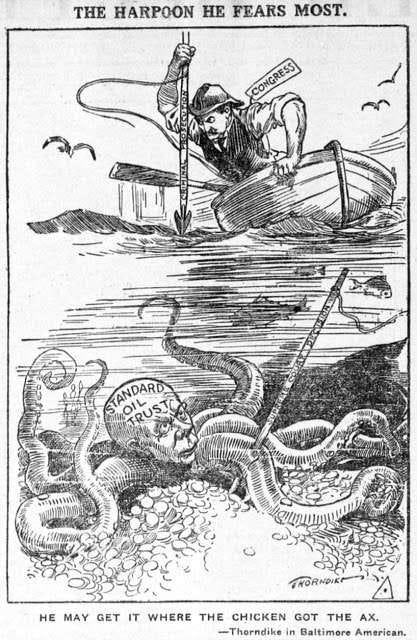

1904 cartoon of Standard Oil

The Octopus

Look closely at this 1904 cartoon, the octopus is Standard Oil and its tentacles are crushing competitors, gripping the White House, and even venturing overseas.

By the end of his lifetime, J. D. Rockefeller’s reputation sank in the court of public opinion as it became clear that he had established a ruthless monopoly called Standard Oil.

Standard Oil’s actions contributed to the introduction of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, a landmark piece of legislation that would curb monopoly power.

But what did Standard Oil actually do? Let's dive into the murky history of oil in America.

Bring me light

John D. Rockefeller founded Standard Oil in 1870. His father was a con man who would sell fake remedies to cure cancer, while his mother was a devout Christian.1

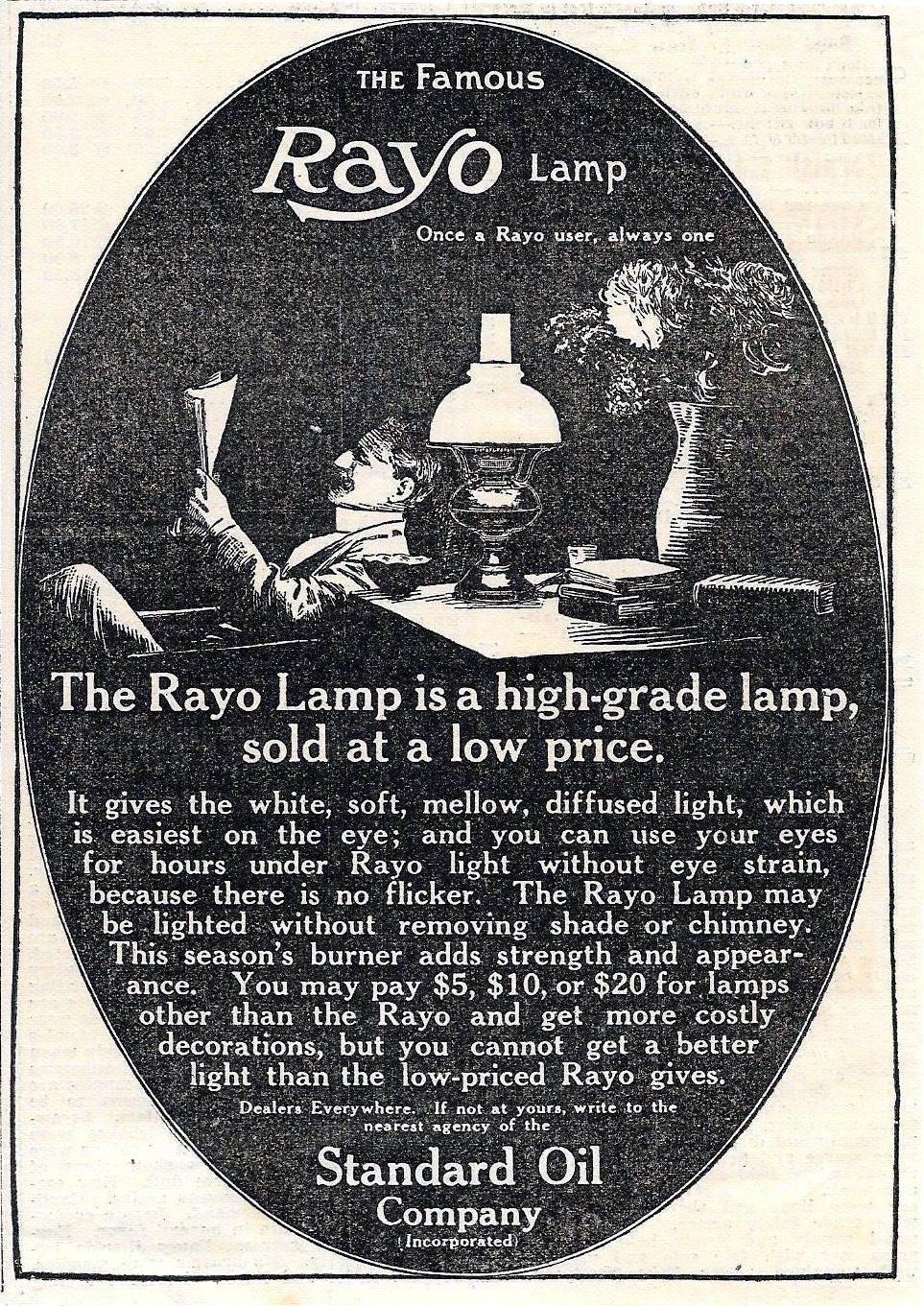

At the time, Standard Oil sold kerosene for oil lamps to provide lighting. Against the backdrop of dangerously variable kerosene quality, Rockefeller’s proposal was to create a standardised and safe product that would not explode unexpectedly. Hence, the name Standard Oil.

A deal you can’t refuse

Rockefeller’s growth strategy was the same as Pac-Man. He would go to independent oil refineries and make a deal they couldn't refuse.

It went like this:

either the refinery could be acquired by Standard Oil and benefit from its shares, or

it could stay independent and face the risk of predatory pricing, where Standard Oil would drive prices into the ground, force its competitors to declare bankruptcy, and then increase prices again to recoup losses.

Most, when faced with such an offer, would accept the acquisition. As more and more accepted, Standard Oil’s ability to influence prices in the market grew, making the strategy even more effective.

“[Standard Oil] has driven into bankruptcy, or out of business, or into union with itself, all the petroleum refineries of the country except five in New York, and a few of little consequence in Western Pennsylvania.” - Henry Lloyd, 1881, The Atlantic

A threatening letter

A similar strategy was used to secure distribution. If a grocery store did not stock Standard Oil’s kerosene, it would allegedly receive a letter which would present a choice: either the shop owner could stock Standard Oil’s kerosene or face the risk of competing with a new grocery store that Standard Oil would open right next to it. Like before, most grocery store owners acquiesced.2

In cahoots with the railways

Rockefeller also offered railway lines guaranteed volume in return for discounts on railway fares. Other oil refineries were charged more per barrel and some of these profits were recycled back to Standard Oil in the form of “drawbacks”.

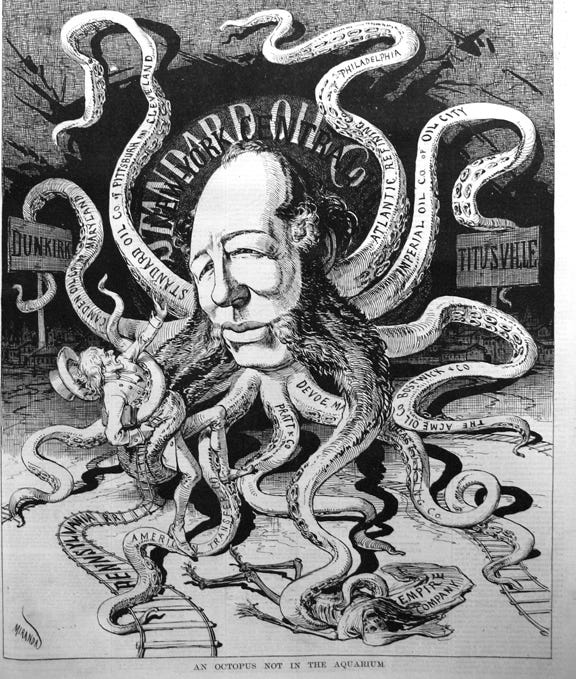

A particularly nefarious structure was the South Improvement Company, a partnership founded in 1872 between three major rail companies, including Pennsylvania Rail Road (pictured in the cartoon below), and Standard Oil.

The South Improvement Company would give Standard Oil control over major transport routes, charge competing oil companies higher rates, and give Standard Oil visibility into its competitors’ operations.

While Rockefeller asserted Standard Oil’s private contracts were his business, there was public outrage over the collusive and anti-competitive nature of the South Improvement Company and it was consequently, quickly dissolved.

Daily Graphic October 23, 1879

A little too late

Rockefeller’s Standard Oil successfully gained control of 90% of the oil refinery market by 1880. The remaining 10% could have come under his control too but it is speculated that he decided to keep up a thin veneer of competition.3

Rockefeller maintained that “industrial combination” would lead to stability in oil prices. Of course this stability also implied singular control by Standard Oil.

He cited the low price of kerosene to justify Standard Oil's actions. While consumers did benefit from this, an important question is what innovation was crowded out and whether Standard Oil was the only route to low prices.

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act

Ultimately, Standard Oil was broken up by the US government in 1911.

“The nation had been rid of human slavery…but… another kind of slavery sought to be fastened on the American people; namely, the slavery that would result from aggregations of capital in the hands of a few individuals.” - Justice John Marshall Harlan, 1911 Supreme Court case against Standard Oil

However, in what would be J. D. Rockefeller’s last laugh, this would actually increase his wealth. Once the public could see the real value of assets that had been accumulated, the value of each offspring company rose. Rockefeller was America's richest man, having a wealth worth 2% of GDP by some estimates.

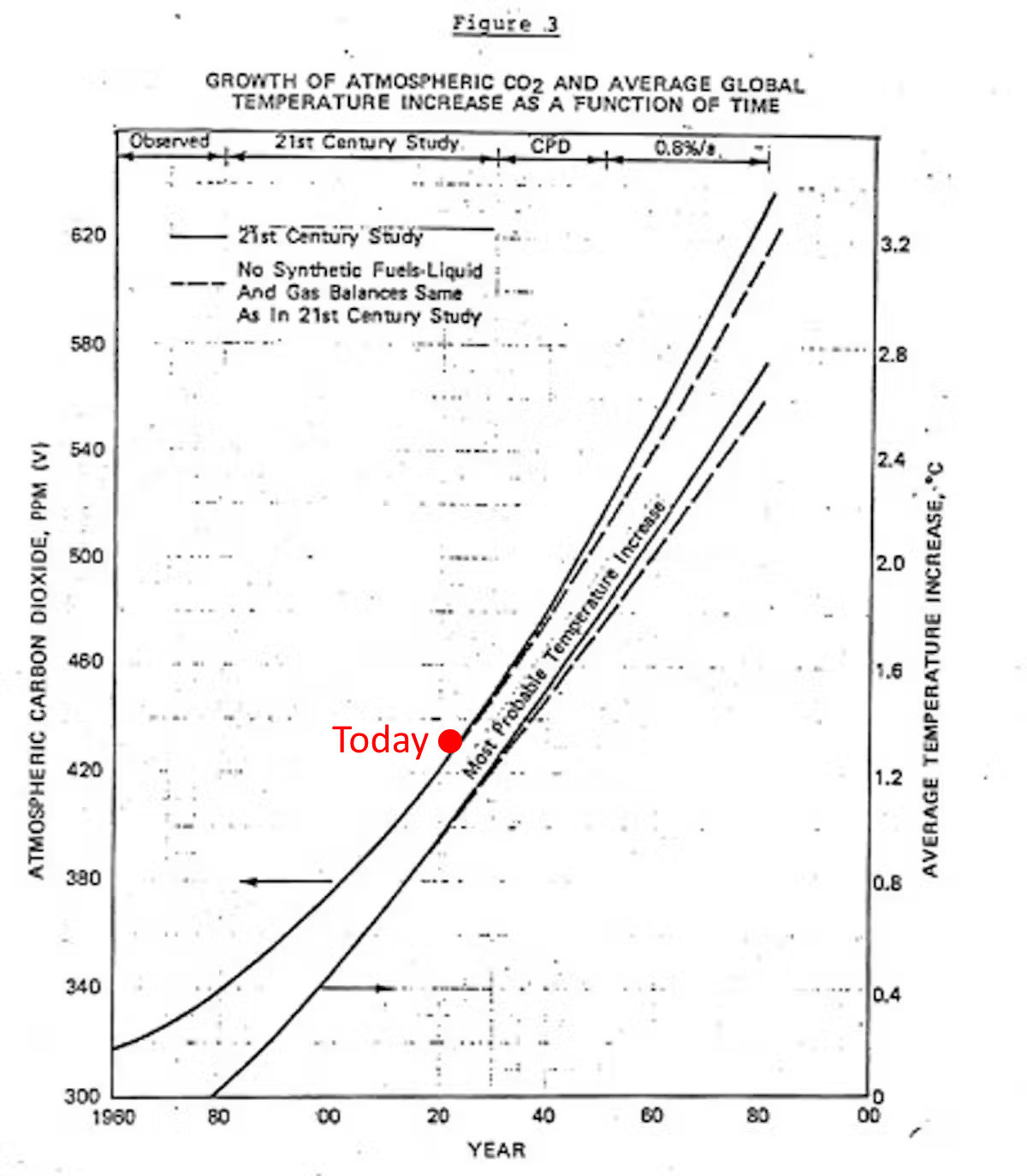

One of the offspring firms was ExxonMobil, a company which would go on to finance large-scale climate denialism while knowing the impacts of climate change, as evidenced by internal documents (see below).4

Exxon’s internal climate change report from 1982, predicting accurately how Earth's temperature will rise due to the activities of the oil industry. Publicly, Exxon cast doubt on climate science.5

The trailblazer

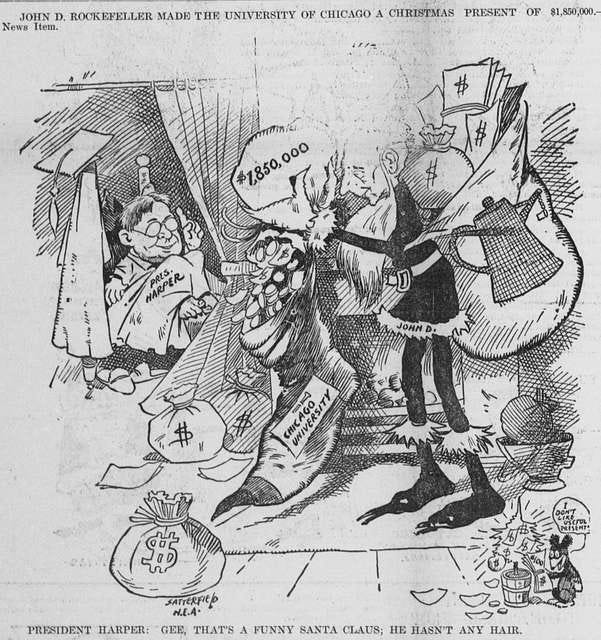

While Rockefeller won financially and would scrub his long-term legacy through copious amounts of charity including founding the University of Chicago, which would go on to present economic arguments around the merits of scale economies and vertical integration, Rockefeller still could not shift public opinion of the time.

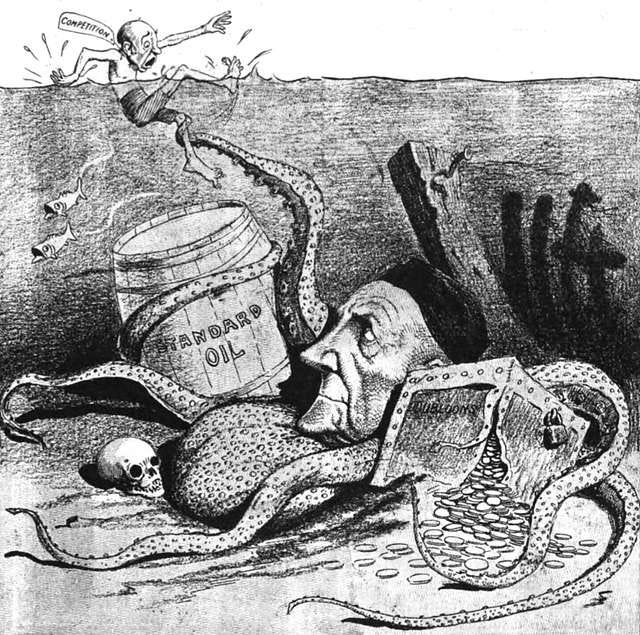

1903 Statterfield cartoon

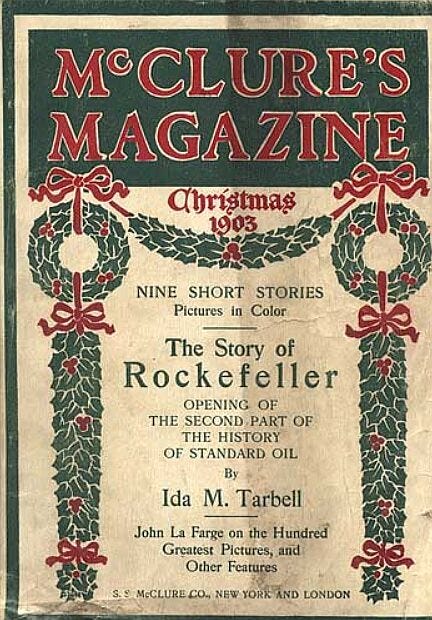

Ida Tarbell, whose father was at the receiving end of Rockefeller’s ruthless tactics, became an investigative journalist and painstakingly brought to light Standard Oil’s practices,6 building on the work of Henry Lloyd and the slew of court cases that Standard Oil left behind. Her trailblazing journalism breathed oxygen into the fire and created the one loss Rockefeller would face: his reputation.

Fair and square?

The oil industry's long-standing narrative is that it exists because of merit: fair and square competition. However, this statement does not align with the facts. History paints a far more complex picture, one in which the rise of oil is intrinsically tied to the exploits of monopoly power.

If the oil industry didn’t undergo such great consolidation, perhaps other technologies would have had a fighting chance. However, once a paradigm is set, then path dependencies and economies of scale kick in and make it hard to exit, regardless of whether the beginning was fair and square.

***

In a future post, I will also explore how many of the exploits of oil companies are tied to colonialism and the extensive concessions that were given by colonies to their colonising nations. Subscribe to stay tuned.

Biography: John D. Rockefeller, Senior. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-john/#:~:text=Rockefeller%20was%20born%20July%208,up%20to%20%2425%20a%20treatment.

Matthew Josephson (1934) Robber Barons.

Henry Lloyd. (1881) The Story of a Great Monopoly. The Atlantic.

Ben Franta (2021). What Big Oil knew about Climate Change in its own words. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/what-big-oil-knew-about-climate-change-in-its-own-words-170642

Ibid.

Elizabeth Catte (2018). Ida Tarbell and the Spirit of Reform. https://beltmag.com/ida-tarbell-standard-oil-spirit-reform/

Thanks for this. The Exon graph says it all. Whilst I am with you with monopolies stifling innovation there is another spin to the story. We are familiar with it. Rockefeller was the quintessential capitalist. He found a great product that everybody wanted, cornered the supply and manipulated demand. And the bit we miss is… ‘that everybody wanted’. If folk had said no to cars, warm houses, copious food etc.. he wouldn't have had any of it. But we didn't and still don't. It's a conundrum.

An excellent read, Sugandha. And very timely.

I have previously enjoyed reading Philippon's 'The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets' which complements your piece from the perspective of today.